In early 2024, central Ohio faced one of its worst tornado seasons in history—66 confirmed tornadoes in less than five months.

But the most lasting damage wasn’t only to homes or power lines. It was to people’s mental health—especially among low-income residents in Franklin County who were already struggling to make ends meet.

The human cost behind the storms

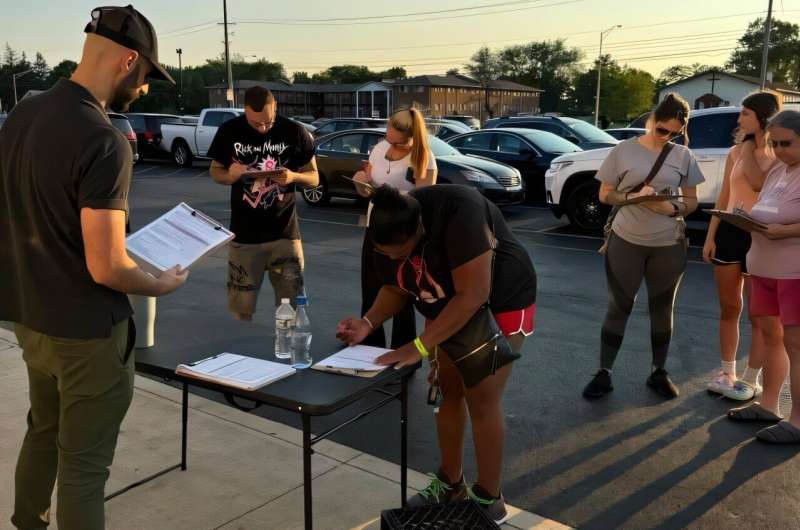

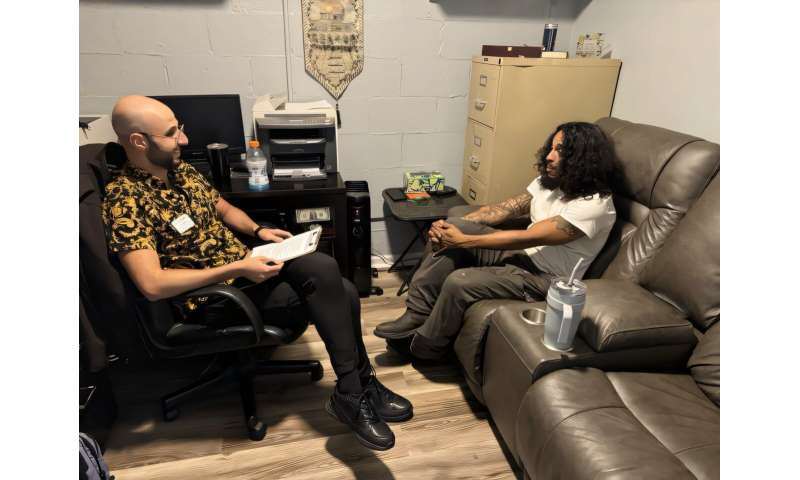

My colleagues and I at Clemson University set out to understand how these disasters affected the emotional well-being of those with the fewest resources to recover. Using surveys from over 500 residents and in-depth interviews with 20 community members, we found a clear pattern: those who suffered the most physical and financial damage also faced the highest levels of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Tornadoes don’t just destroy buildings—they unravel stability

For many participants, every storm warning brought fear and dread. “Every time there’s a storm, I get really anxious. I worry about the kids,” one mother told us.

Others described isolation and financial strain as the biggest triggers for their mental health struggles. Rising utility bills and property repairs drained already tight budgets, while disrupted transportation and housing instability deepened their sense of helplessness.

Our data showed that people who experienced the most damage were two to three times more likely to report severe symptoms of anxiety and depression. Nearly 40% exhibited signs of PTSD—double the rate of those less affected. These aren’t abstract numbers; they represent people losing sleep, feeling unsafe in their own homes, and worrying that the next tornado season will bring something even worse.

Coping, resilience, and small acts of strength

Amid these struggles, we also witnessed resilience. Family and community networks played a crucial role. Many relied on relatives, churches, and food pantries to share resources and emotional support. Some found strength in mindfulness or faith-based routines; others turned to less healthy coping mechanisms, such as substance use, when mental health services were out of reach.

These stories highlight a difficult truth: coping mechanisms are shaped by access. Without affordable counseling or community support, stress can easily transform into chronic anxiety or depression. Yet, where community bonds were strong, people reported greater hope and emotional stability, even when their material losses were significant.

What communities and policymakers can do

Our findings suggest that preparing for future disasters must go beyond rebuilding physical infrastructure—it must also include building psychological resilience. Local governments and community organizations can take practical steps:

- Expand access to affordable mental health care, including telehealth and mobile counseling units.

- Offer community-led resilience workshops on stress management and emergency preparedness.

- Improve risk communication, ensuring that warnings are timely, consistent, and actionable for residents with limited resources.

- Support financial relief programs, such as utility and rent assistance during extreme weather seasons.

If these steps are integrated into disaster preparedness planning, communities can not only survive the next storm—but emerge stronger from it.

The bigger picture: Climate, inequality, and the future of mental health

What we saw in Franklin County is part of a larger national trend. As climate change fuels more frequent and intense weather events, the people hit hardest are those with the fewest resources to adapt or recover. Low-income families often live in older, poorly insulated homes, with limited access to insurance or savings.

When disasters strike, the emotional burden compounds quickly—worrying about rent, repairs, and safety becomes a constant cycle of stress.

Our study adds to growing evidence that climate resilience must include mental health resilience. If communities are not emotionally and psychologically prepared, recovery efforts risk deepening existing inequalities. Mental health must become a core pillar of climate adaptation—not an afterthought.

-

Team collecting data from low-income communities. Credit: Amer Abukhalaf

-

Team collecting data from low-income communities. Credit: Amer Abukhalaf

A call to listen: What survivors taught us

What stood out most in our interviews wasn’t just the hardship—it was the honesty and humanity of the stories people shared. Many participants told us they had never been asked how the storms affected their mental health before. Listening to them revealed a powerful truth: healing begins when people feel heard.

Disaster research often focuses on data, but behind every percentage point of anxiety or depression is a person rebuilding their life while holding their family together. As researchers, policymakers, and citizens, we must ensure that these voices guide how we design recovery programs. True resilience starts with empathy, and empathy begins with listening.

Why this matters now

Climate-related disasters are intensifying across the U.S., and their psychological toll will grow unless we address these social and economic inequities. My research shows that mental health recovery after disasters is not just a medical issue—it’s a matter of social justice.

By understanding how storms affect our minds as much as our landscapes, we can design fairer, more compassionate systems for resilience.

This story is part of Science X Dialog, where researchers can report findings from their published research articles. Visit this page for information about Science X Dialog and how to participate.

More information:

Amer Hamad Issa Abukhalaf, et al. Mental Health Impacts of the 2024 Ohio Tornadoes on People With Socioeconomic Disadvantages (2025). hazards.colorado.edu/health-an … onomic-disadvantages

Amer Abukhalaf is an assistant professor at the Nieri Department of Construction and Real Estate Development, Clemson University. Abukhalaf is also a faculty scholar at the Clemson University School of Health Research. He researches risk management and safety design with a focus on natural hazards, built environment, crisis management, and emergency planning. Abukhalaf is also a civil engineer and a structural designer by practice and has a master’s in executive management from Ashland University in Ohio, and a Ph.D. from the University of Florida. He is a member of the Hazard Mitigation and Disaster Recovery Planning Division at the American Psychological Association.

Citation:

Invisible wounds of the Ohio tornadoes: The mental health crisis after the storm (2025, October 25)

retrieved 26 October 2025

from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2025-10-invisible-wounds-ohio-tornadoes-mental.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.